Understanding Surface Roughness and Surface Finish

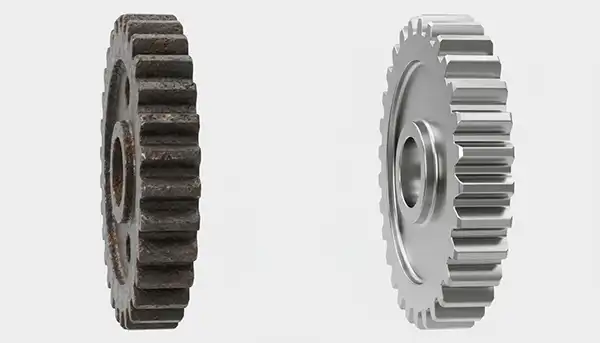

Ever handed off a perfect design only to get back a part that just doesn't feel or work right? The dimensions are spot-on, but it's too tight, too loose, or wears out prematurely. Chances are, the culprit is often surface finish. In simple terms, surface roughness describes how smooth or textured a machined surface really is.

Understanding surface roughness isn't just for machinists; it's crucial for engineers, designers, and anyone who cares about how a part functions in the real world. This guide will demystify surface roughness charts, symbols, and measurements, turning you from a beginner to a confident professional.

Quick Reference Cheat Sheet (TL;DR)

-

Common Ra Values:

-

25 µm (1000 µin): Rough, saw-cut surface.

-

3.2 µm (125 µin): Standard machined finish, visible tool marks.

-

1.6 µm (63 µin): High-quality machine finish, smooth to the touch.

-

0.4 µm (16 µin): Very smooth finish, for bearings and sealing surfaces.

-

What is Surface Finish?

At first glance, a machined surface might look smooth. But under a microscope, it’s a landscape of peaks and valleys. Surface finish (also known as surface texture or surface roughness) is the measure of this textured topography.

Think of it like the grain of wood. Sometimes you want a rough, grippy texture (like a skateboard deck), and other times you need a glass-smooth surface (like a furniture tabletop). Metal parts are the same.

A surface profile is made up of:

-

Roughness (Ra/Rz): The fine, closely-spaced peaks and valleys from the manufacturing process itself (e.g., the cutting tool's mark).

-

Waviness (Wa/Wt): The more widely spaced undulations on the surface, usually caused by machine vibration or heat warping. Think of it as the "rolling hills" that the roughness sits on top of.

-

Lay: The dominant direction of the surface pattern, like the "grain."

Why is Surface Finish So Important in Engineering?

Specifying the right surface finish isn't about being picky; it's about function, cost, and performance.

- Fatigue Life: A rough surface is full of microscopic cracks and stress concentrators. A smoother finish significantly improves a part's resistance to fatigue and cracking under repeated loads.

- Wear and Friction: Two rough surfaces sliding against each other will wear out quickly. A controlled, smooth finish reduces friction and wear, extending the life of moving parts.

- Sealing: Whether it's a hydraulic piston or a flange face, a surface that's too rough will leak fluid or gas. A surface that's too smooth might not retain lubrication. The "right" finish creates a perfect seal.

- Coating and Adhesion: Paints and coatings adhere much better to a surface with a specific, controlled roughness.

- Aesthetics: Let's be honest - a part with a uniform, attractive finish just looks more professional.

Key Surface Roughness Parameters: Ra, Rz, and More

You'll see letters like Ra and Rz on engineering drawings. These are parameters that give a number to the roughness. Here are the key players:

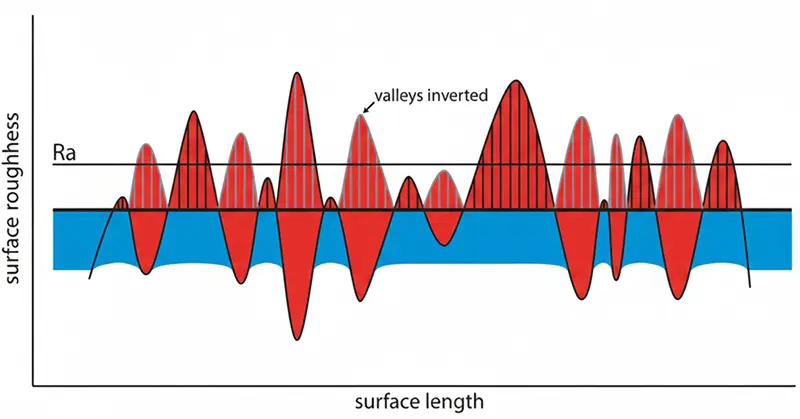

Ra - Arithmetic Average

Ra is the most common parameter. It calculates the average of the absolute values of the profile heights over a length.

-

Simple Explanation: It's the "average" height of the bumps and valleys. It gives a good overall picture but doesn't distinguish between sharp, spiky peaks and gradual, rolling hills.

Rz - Average Maximum Height

While Ra is an average, Rz measures the average distance between the highest peak and the deepest valley in five sampling segments. It's better at catching extreme variations that Ra might smooth over.

-

When to use it: For surfaces where peak-to-valley height is critical, like in sealing applications or for preventing stress concentrations.

| Parameter | What It Measures | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Ra | The average roughness over the evaluation length | General‑purpose surface specification; most common callout |

| Rz | The average peak‑to‑valley height over several sampling lengths | Applications where extremes matter (sealing, stress‑critical areas) |

| Rq | Root mean square (RMS) roughness | Legacy specs, comparison with older drawings |

| Rmax | The single largest peak‑to‑valley height | Critical surfaces where no large defects are allowed |

How to Measure Surface Roughness

You can't manage what you can't measure. Surface roughness is quantified using precise instruments.

The Various Methods of Measurement

-

Contact Profilometer: This is the most common method. A very fine, diamond-tipped stylus is dragged across the surface. As it moves over the peaks and valleys, the stylus's vertical movement is recorded and converted into a roughness value.

-

Pros: Accurate, reliable, and the established standard.

-

Cons: Can be slow and the delicate stylus can be damaged.

-

-

Non-Contact Profilometer: These use optical techniques like lasers or white light interferometry to map the surface without touching it.

-

Pros: Extremely fast and perfect for soft or delicate surfaces that a stylus might scratch.

-

Cons: Can be more expensive and sometimes struggles with very shiny or transparent materials.

-

-

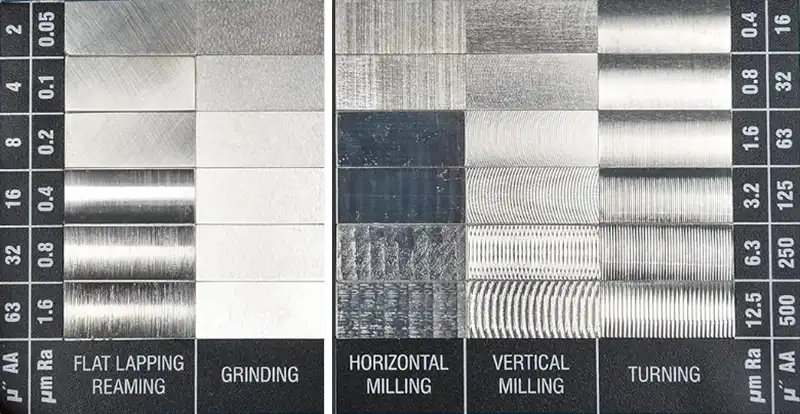

Comparative Sample Kits: This is a practical, low-tech method. The inspector has a set of physical samples with known roughness values. They compare the feel and look of the manufactured part to the samples by sight and touch (often with a fingernail).

-

Pros: Quick, inexpensive, and great for shop-floor checks.

-

Cons: Subjective and not suitable for critical inspection.

-

Understanding Cutoff Lengths (Sampling Length)

While Ra and Rz values tell you how rough a surface is, the cutoff length (often denoted as λc) tells the measurement instrument what to measure.

Think of a surface profile like a rolling landscape. You have tiny rocks (roughness) sitting on top of larger hills (waviness). The cutoff length acts as a filter:

- Shorter Cutoff (e.g., 0.08 mm or 0.25 mm): Filters out waviness to focus only on very fine roughness. Used for super-smooth surfaces like mirrors or honed cylinder bores.

- Standard Cutoff (0.8 mm): The industry standard for most machined parts (Ra 0.4 µm – Ra 3.2 µm). If no cutoff is specified on the drawing, 0.8 mm is the default.

- Longer Cutoff (2.5 mm or 8.0 mm): Used for rougher surfaces (like castings or flame-cut edges) to ensure the measurement averages out enough of the surface to be representative.

Why it matters: If you measure a rough surface with a cutoff that is too short, you will get an inaccurately low Ra value, potentially passing a bad part.

Surface Roughness Chart Symbols and Abbreviations

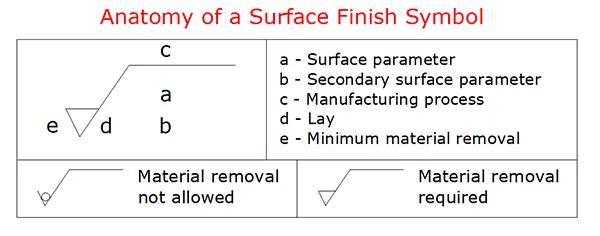

The symbols on an engineering drawing give a wealth of information beyond just a number.

Here’s a cheat sheet for the most common symbols:

-

Basic Symbol: The check mark. It simply indicates that a surface has a specified texture requirement.

- Circle in the V (per ISO 1302 convention): A circle means "the surface must be produced by material removal." In other words, no cast, forged, or molded surface is allowed.

-

Bar on the V (per ISO 1302 convention): A horizontal bar means "the surface must be produced without material removal." This is for a critical as-cast or as-forged finish.

-

The Full Callout: Around the symbol, you'll find:

-

The roughness value (e.g., Ra 1.6)

-

The manufacturing process (e.g., "Grind"), if specified.

-

The lay direction (see below).

-

The sampling length.

-

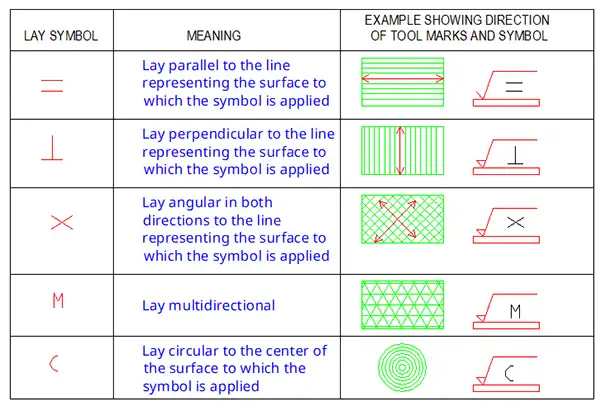

Lay Direction Symbols

The lay is the direction of the predominant surface pattern, and it's represented by a symbol inside the check mark.

The Surface Roughness Chart

This chart links common Ra values to their typical appearance, manufacturing process, and application.

| Ra (µm) | Ra (µin) | Appearance | Typical Process | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 1000 | Very rough | Saw cutting, rough forging | Unfinished parts, non-critical surfaces |

| 12.5 | 500 | Rough | Rough machining, drilling | Non-mating surfaces, rough stock |

| 6.3 | 250 | Clearly visible tool marks | Standard milling, turning | Non-critical bearing surfaces, bolt holes |

| 3.2 | 125 | Visible tool marks | General machining | Parts under stress, sliding surfaces |

| 1.6 | 63 | Smooth, slight marks | Precision machining, reaming | Hydraulic cylinders, bearing seats |

| 0.8 | 32 | Very smooth, no visible marks | Grinding, honing | Gears, crankshafts, precise sliding parts |

| 0.4 | 16 | Near‑mirror finish | Precision grinding, lapping | Ball bearings, precision instruments |

| 0.2 | 8 | Mirror‑like finish | Polishing, superfinishing | Optical components, gauge blocks |

Surface Finish Conversion Chart

Need to convert between Ra, Rz, and other parameters? Use this chart as a guide. Important Note: These are approximations, as Ra and Rz measure different things. For critical applications, always refer to the primary standard.

| Ra (µm) | Ra (µin) | Rz (µm) approx. | ISO Grade Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.025 | 1 | 0.1 | N1 |

| 0.05 | 2 | 0.2 | N2 |

| 0.1 | 4 | 0.4 | N3 |

| 0.2 | 8 | 0.8 | N4 |

| 0.4 | 16 | 1.6 | N5 |

| 0.8 | 32 | 3.2 | N6 |

| 1.6 | 63 | 6.3 | N7 |

| 3.2 | 125 | 12.5 | N8 |

| 6.3 | 250 | 25 | N9 |

| 12.5 | 500 | 50 | N10 |

| 25 | 1000 | 100 | N11 |

Surface Roughness Comparison Guide: Choosing the Right Finish

This is where theory meets practice. How do you choose?

-

For a Static Gasket Seal: You need a flat surface with just enough "bite." A finish that is too smooth can be as bad as one that is too rough. A range of Ra 1.6 - 3.2 µm is often ideal.

-

For a Rotating Shaft in a Bearing: A very smooth finish is needed to prevent wear and heat buildup. Aim for Ra 0.4 - 0.8 µm.

-

For a Structural Weldment: A non-critical surface that will be painted. A finish of Ra 6.3 - 12.5 µm is perfectly acceptable and cost-effective.

The Golden Rule: Always specify the roughest finish that will perform the required function.A smoother finish always means more machining time, specialized processes, and higher cost. Moving from Ra 3.2 to Ra 0.8 could easily double the cost of that surface's machining.

Your Surface Roughness Chart Cheat Sheet

Let's condense everything into a few key takeaways:

-

Start with Ra: For most applications, specifying Ra is sufficient.

-

Know Your Numbers:

-

Ra 3.2 µm: Your standard, go-to machined finish.

-

Ra 1.6 µm: A high-quality finish for mating surfaces.

-

Ra 0.8 µm: A precision finish for dynamic components.

-

-

Understand the Symbols: A circle in the symbol means “must be machined by material removal.” The basic check mark means a surface requirement exists, even if the process is not specified.

-

Consider the Cost: Every step down in roughness value is a step up in price.

Conclusion

Mastering surface roughness is a superpower in mechanical design and manufacturing. It is the difference between a part that works and a part that excels. By using this guide, the charts, and the cheat sheet, you can now specify surface finishes with confidence, ensuring your designs are not only functional but also efficient and cost-effective to produce.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between Ra and Rz?

Ra is an average height, while Rz is the average maximum peak-to-valley height. Ra gives a general picture, while Rz is better at capturing extreme variations.

What is a "standard" surface finish for CNC machining?

For most CNC milling and turning, a finish of Ra 3.2 µm is considered standard and is achievable directly from the tool without secondary operations.

Can I perfectly convert Ra to Rz?

No. The conversion is not a perfect 1:1 ratio because they measure different geometric properties. The charts provide close approximations, but for critical features, you should specify and measure the exact parameter you need.

What does a surface finish of 0.8 mean?

It means an Ra value of 0.8 micrometers (µm). This is a very smooth, high-precision finish typically achieved by grinding or honing.

Can different surfaces of the same part have different finishes?

Yes, and this is actually very common in manufacturing. Different surfaces on the same part often require different finishes based on their function. For example, a shaft might need Ra 0.8 µm on the journal surfaces that contact bearings for smooth rotation, Ra 3.2 µm on mounting faces that need good sealing, and Ra 6.3 µm on non-critical exterior surfaces. Specifying different finishes saves money by only applying tighter (more expensive) finishes where functionally necessary. On your drawing, simply place the appropriate surface finish symbol on each surface or use a general note like "Ra 6.3 unless otherwise specified" with specific callouts where finer finishes are needed.

What is the difference between surface finish and tolerance?

Surface finish and tolerance are two distinct specifications that control different aspects of a part. Tolerance defines how much a dimension can vary from its nominal value (for example, 50mm ±0.1mm controls size), while surface finish describes the texture or roughness of the surface itself (for example, Ra 3.2 µm controls smoothness). You can have a part that's within dimensional tolerance but has the wrong surface finish, or vice versa. Both are specified independently on engineering drawings - tolerances appear next to dimensions, while surface finish symbols appear on or near the surface features they control.